Part 1: Trust

Aug 03, 20211. Could People in the Roman Empire Trust One Another?

In the New Testament we find few professions (or occupations) mentioned. The first of these few to come to mind is that of Paul, Priscilla, and Aquila, all “tentmakers.” One among those few professions mentioned is normally overlooked, “thief” (Eph 4:28). The Christian exhortation in Ephesians is against thievery, but thievery does seem to have been a way to make a living in the major cities of the Roman Empire. Juvenal (Satire 8) makes fun of an army leader by saying he consorts with people who practice disreputable occupations:

But look for your general in some great tavern. You will find him reclining with some common cut-throat; in a medley of sailors, and thieves, and runaway slaves; among executioners and cheap coffin-makers, and the now silent drums of the priest of Cybele, lying drunk on his back. . . . what would disgrace a cobbler will be becoming in a Volesus or Brutus! [1]

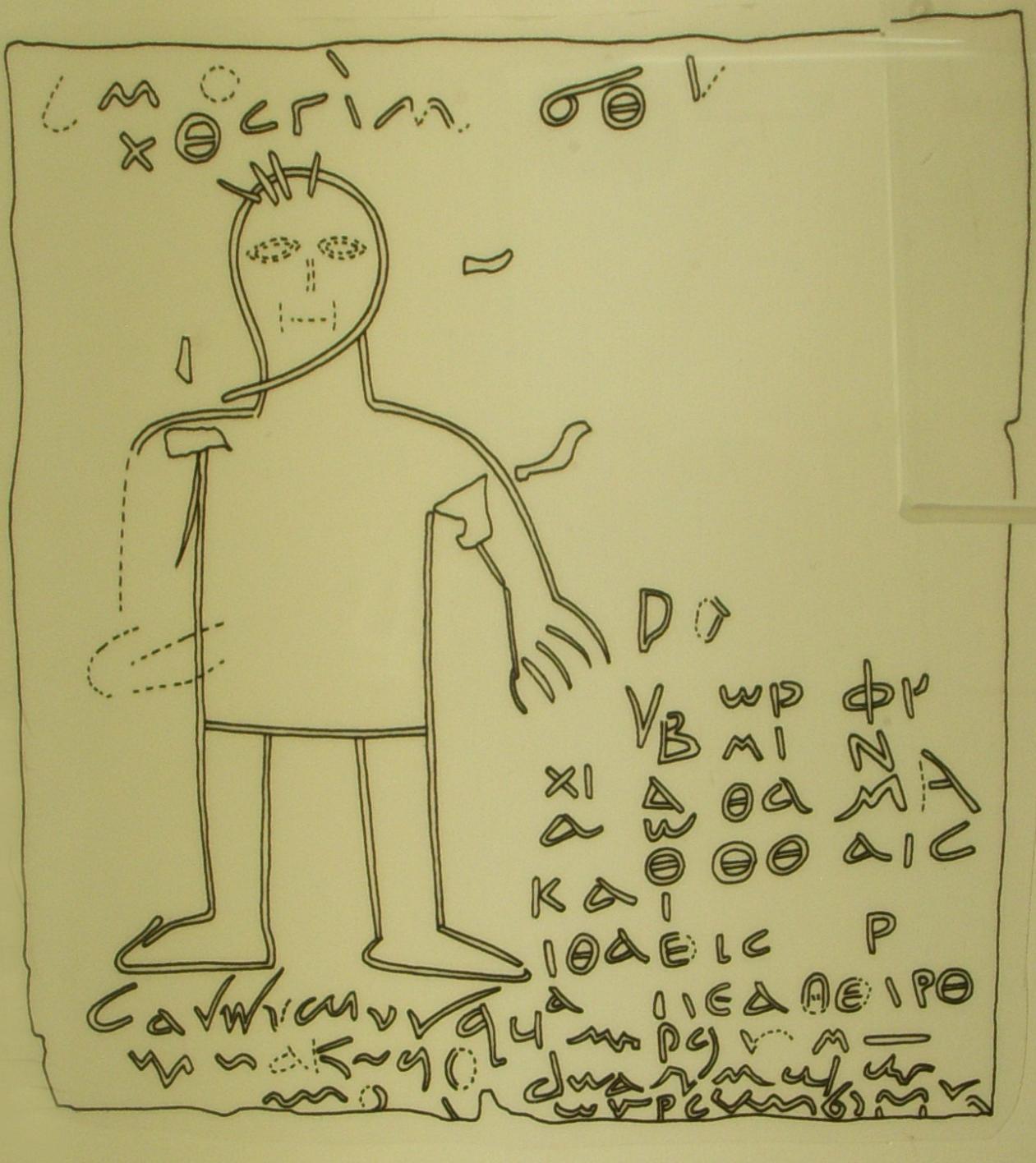

A - Curse against Cassinus who hired malicious women

– From the Roman National Museum (Baths of Diocletian).

Beyond this mention of sailors, thieves, runaway slaves and cobblers, Evans gives us a note to the poetic translation of Stepney (in Dryden's version) which adds some disreputable occupations to the list: "Quacks, coffin-makers, fugitives, and sailors,/Rooks, common soldiers, hangmen, thieves, and tailors."[2] No doubt some occupations were added to make the rhyme in English, but those added were among those commonly thought to be practiced by untrustworthy people. Some of these professions were “honest”: sailors and cobblers, and probably coffin makers, were engaged in honest professions. However these were not highly regarded. Maybe “tentmakers” were not highly regarded either, although it was certainly an honest profession.

Ramsay, when mentioning St. Paul in Athens, made reference to “those disreputable persons who hang round the markets and the quays in order to pick up anything that falls from the loads that are carried about.”[3] Ramsay’s point is that the elite scholars of Athens had no regard for Paul, just as they had no regard for scavengers, but in our consideration of Roman society we wonder how wide-spread the profession of scavenging was. Maybe very wide-spread, and if so, why? We need to ask if many were unable to “earn” a living except by scavenging.

Scavengers, like thieves and executioners, were not honest. Likewise, “quacks” might refer to pharmakoy, people who sold drugs, including poisons, and also engaged in various sorts of witchcraft. Reading ancient documents that make reference to ways people “earned” their living suggests that there were many people in the great cities of the Roman Empire that one could not trust. In the New Testament we read that there will be no night in Heaven. (Rev. 22:5.) This is a hopeful promise for anyone who experiences the dark hours of night as a time when thieves and cutthroats are likely to accost you.

How much joy can be found in an environment in which you cannot trust those you meet?

[1]Juvenal (Decimus Junius Juvenal, Aulus Persius). (tr. Lewis Evans). The Satires of Juvenal, Persius, Sulpicia, and Lucilius literally Translated into English Prose. NY: Harper & Brothers, 1881. [December 10, 2015 EBook #50657 https://www.gutenberg.org/files/50657/50657-h/50657-h.htm]

[2] Footnote #463.

[3] Ramsay, William M. St. Paul the Traveller and the Roman Citizen. (3rd ed.) London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1897, p. 242.